Curtains are ‘hung’, a pirate is ‘hanged’; such are the quirks of the English language. Hanging is not a pleasant way to die. No execution is pleasant, but until the ‘long drop and the short stop’ was introduced it could take anything up to twenty minutes to slowly strangle to death with ejaculation and bowels and bladder evacuating the body. Death could be quicker if weight was added, so family and friends would ‘hang on’ to the victim’s legs and torso to speed up the process. Which is where the term ‘hangers on’ comes from.

The ‘hempen jig’ refers to the body jerking in those last moments of life suspended from a hemp rope, and Jack (or John,) Ketch became a name synonymous with hanging. Employed by Charles II in the late 1600s he is first mentioned in London’s Old Bailey proceedings as a public executioner in 1676. In addition to hangings he was responsible for overseeing burnings and beheadings, two of which he bodged so badly he later had to publish a public apology. He executed Lord William Russell by beheading in 1683, the accused sentenced to death at Lincoln’s Inn Fields, London, in July 1683 for plotting against King Charles II. Ketch struck the axe four times before successfully decapitating him. Then in July 1685, following his failed rebellion against King James II, he similarly botched the beheading of James Fitzroy Scott the Duke of Monmouth, Charles II’s eldest illegitimate son at Tower Hill, taking between five to eight repeated blows in a brutal manner to do the task. Ketch is mentioned in several novels (including my own) and in Dickens’ Oliver Twist, Pickwick Papers and David Copperfield.

The most well known places of execution in London were Tyburn, located near the current position of London’s Marble Arch; Tower Hill close to the Tower of London and Wapping alongside the River Thames, used for pirates, as was Port Royal in the West Indies. An estimate of more than 60,000 souls were executed at Tyburn between the end of the 12th century and the close of the 18th, most being under the age of twenty-one.

The purpose of public executions was to discourage crime and to demonstrate the power of the law to the populace. Hangings at Tyburn took place eight times per annum and was conducted in a sombre and severe way in order to enhance the deterrent to committing crime. In other places, notably Port Royal, Nassau and Williamsburg in Virginia the sentence could be carried out within four-and-twenty hours, if not immediately.

|

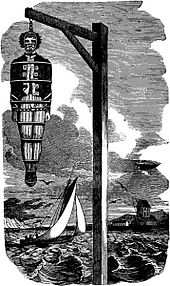

| Execution at Wapping |

Execution day was a public event, an entertainment. Crowds would gather, entire families – children too. Pie-men, cake sellers, drink sellers, every seat taken in the taverns and coffee shops. Prostitutes touting their wares would be busy, their employment heightened by the air of excitement. Pamphlets of written confessions would be on sale, no one bothered to ask if they were fact or fiction.

Think of your local outdoor event, a fair or County Show maybe, with the press of people out to enjoy themselves and tradesmen hoping to make a nice profit. The cutpurses and street entertainers will be there; lots of noise and bustle, shouting, laughter. An argument or two with pushing and shoving for a front row view. For that is the main attraction, the thing they have all come to see. Not a pop or film star, not Royalty passing by in a gold coach, not the latest-trend magician attempting some seemingly impossible trick, but the wooden frame of the gallows was the centre of attention, and the man, or woman, who was about to ‘dance’ beneath it.

On execution day the prisoner would be released from the shackles which had restrained him, possibly for many months. His wrists and ankles sore, the flesh swollen the tethering would be replaced with a leather cord or wrist chains. A leather halter would be fitted around the neck and he or she would either walk or be taken by cart (depending on the distance) to the place of execution. If the procession passed a church or chapel the victim would be permitted an opportunity to pray. Crowds would line the route, jeering and yelling. The more unpopular the criminal, or his crime, the louder the noise.

Making a brave end was essential for good will. The crowd could turn nasty against those who showed fear, while the brave-faced, especially those who uttered subversive, derisive or bold speeches were admired. Even more so those who displayed an air of showmanship by jesting with the audience or offering a confession that contained lurid and graphic detail went down well. To provide a good entertainment meant obtaining immortality within a pamphlet or column in the news sheets. Glory is a funny thing.

What the condemned wore was also important. They were permitted to wear what they chose, the better the quality the better for the executioner for he would later sell the clothes for a handsome profit, unless the victim was to be gibbetted in an iron cage after death. Even then it is doubtful that anything flamboyant would be displayed for many months on a rotting corpse. The fine clothes would be surreptitiously swapped for something less ostentatious. Many pirates loved colour and trinkets, wearing jewellery – brooches, rings, necklaces, earrings and ribbons in their hair they hoped to convey a dashing, rich and successful figure. King Charles I of England elected to wear several shirts for his public beheading in order that he might not been seen to shiver, for it was a cold day and he did not want to be thought of as shaking from fear.

Hannah Dagoe cheated the hangman out of his extra money by stripping off her clothes as she walked to the gallows, tossing bits of finery to the admiring crowd, arriving at the place of execution with very little on. She then further insulted the hangman by kneeing him in the groin and jumped out of the cart breaking her own neck as she hanged. Many of the condemned, far from showing remorse or proving crime did not pay, became celebrity heroes.

Children as young as seven could be hanged for a capital crime, of which there was no less than 222, including damaging Westminster Bridge! The number was reduced to four offences in 1861, these being murder, arson in a royal dockyard, treason and piracy. The death penalty, in Britain at least, was not abolished until 1969 but this was only for murder, however, the other three remained until the European Convention on Human Rights in 1999 ratified a law that all death penalties were to be abolished. The last public hanging outside Newgate Prison was in May 1868, and the last public execution of a woman was at Maidstone that same year.

The change to the drop and the rope being knotted in such a way that the neck is broken and the jugular vein ruptured is not necessarily a ‘kinder’ way to kill, although it is quicker. The truth is, there is no way of knowing how long or short a time the person feels pain. Death by hanging is supposedly ‘almost instantaneous.’ The word ‘almost’ is a little alarming. Sentencing carries the words ‘hanged by the neck until dead.’ A Canadian in 1919 took over an hour to be hanged by the neck until he was dead. There were also cases of the head being snapped off. Nasty.

Anything could be used for a gallows, often a sturdy bough was ideal for the job with the unfortunate victim being ‘turned off’ from a ladder, stool, back of a cart or a horse. Most towns erected a gallows either in the town centre or at a crossroads just outside, the conventional structure being a single upright with a beam cross-braced at a right angle, or two upright posts joined by a beam for dispatching more than one person at once. Both required a ladder, stool, barrel or cart for the hanged person to stand upon.

|

| The Tyburn 'Tree' |

The ‘triple tree’ was erected at Tyburn, a triangular-shape from uprights of about twelve feet high and crossbeams, where up to twenty-four could be hanged at once.

The ‘drop’ gallows came into use at Newgate in 1783, consisting of a box which the victim stood on, then it dropped down leaving him or her suspended and strangling. The ‘box’ was eventually replaced by a trapdoor. Until 1892 the prisoner’s hands were usually bound in front, with the cord around the wrists and a second one encircling the body and arms. This was so that they could pray until that final moment. It was not until the 1890s that arms were restrained behind the back. Not until 1856 were legs or ankles tied. Hoods to obscure the face from public view were not used until the 1800s. The noose was initially a hemp loop, but when the end was threaded through a brass eyelet it became easier to run, and therefore tighten quicker. The position of the eyelet, beneath the angle of the jaw, was vital in order to ensure the head moved backwards to break the neck, not forwards to constrict the throat.

The rope itself, after it had done its job, would be cut into short lengths by the hangman and sold as souvenirs. As, all too often, were the body parts, or even the entire cadaver to be used by medical men and students for dissection. One body, thus disposed of, was laid out on the dissecting table only to ‘come alive’ as proceedings began. This was not a one-off occurrence. All who were found to be alive were reprieved, presumably as their survival constituted an act of God’s intervention. From the 1st of June 1752, mandatory dissection for murderers, men or women, came into being with an Act of Parliament. The Act was abolished in August 1832. The family of the deceased were also able to buy the body if they had enough funds to bribe the hangman. In the 1600s and 1700s he was more often than not a criminal himself, who had been reprieved with the condition that he executed others who had been condemned. For this reason it is very rare to have the hangman’s name or identity recorded.

Where an example had to be made, particularly in the case of pirates, gibbeting, or hanging in chains was an additional sentence. After death the criminal would be stripped naked, the body coated in hot pitch or tar and when it had set hard, be re-dressed and secured in an iron cage. The entire structure was then attached to the gallows from which the culprit had ‘swung’ or a gibbet that had been erected in a prominent place especially for the purpose. The idea was to display a stark reminder of the fate awaiting the lawless. It does not seem to have worked very well as a warning. The corpse remained there until it was either eaten by birds and rats or rotted away. The risk of having your corpse gibbetted, or dissected, made no difference to the manner of execution, but for the religious hanging in chains and dissection meant a great deal, for it was believed a body was needed to be able to reach heaven. Even if not especially religious in life, belief in God and an afterlife often meant much when someone was about to meet his or her maker. The punishment signified no reprieve even after death but continuous torment for the soul.

I wonder how many pirates actually cared about that?

I wonder how many pirates actually cared about that?

|

| Buy from Amazon |

|

| Buy from Amazon |

Years ago I read the autobiography of Albert Pierrepoint, the last British hangman. Morbidly fascinating!

ReplyDeleteGreat article and surprisingly helpful! (I know this is much later lol, but I just wanted to say thanks for the info).

ReplyDelete