A Guest Post by Nicky Galliers

Parchment, or vellum as I am going to refer to it, is an amazing material and one that is poorly understood. Yet few realise how little they understand it.

There have been many writing substrates through the millennia: stone, papyrus, wax, slate, vellum, paper and others besides. Paper is the most familiar, obviously, but that makes us think we also know about vellum. Vellum looks like paper, does the same job as paper, we think it does what paper does, only in a more old fashioned way.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

To assume vellum and paper are practically the same is to assume that a horse and a scooter are the same because they are both forms of transport. Few people truly understand the marvellous, almost magical, material that is vellum.

Vellum is a natural product, more natural than many a bleached, processed paper. Today it is the by-product of the food industry, from skins that would otherwise be disposed of by being burned, causing harm to the environment. In the past sourcing wouldn’t have been limited to the food industry.

Today, each carefully selected skin is cleaned, bleached if necessary - many skins are selected for the natural characteristics and colour - stretched on a frame called a herse, resulting in a 25% increase in surface area, and left to dry. Once dry, it is removed from the herse, smoothed and then trimmed into sheets.

There are many qualities that vellum possesses that makes it a rather astonishing material. Its very toughness has been exploited over the millennia for more than just writing on. It won’t tear, won’t break, snap or disintegrate like paper. It takes 500 years for it to discolour, if it is going to.

Another quality is its inflammability; you can’t set it alight. It doesn’t carry a flame. Hold a flame to it for long enough, yes, it will start to degrade, but it won’t catch, so when the flame is removed, the vellum stops burning. This means that to destroy a piece of vellum takes a bit longer than paper and a bit more effort. You can’t just shove the corner in a candle flame and leave it to it – as soon as you move the flame away, it all stops. To fully burn a sheet of vellum you have to apply the flame to the whole sheet. You can drop it in a fire, a piece I dropped on a barbecue charred and curled quickly but not as quickly or thoroughly as paper. I was able to remove it and it wasn’t hot to touch. It is medieval Nomex or Proban, the materials that race drivers and circuit marshal wear to protect them from flame. A word of warning for those who want a character in a book to get rid of some vellum in an underhand manner by burning – it stinks!

If fire is not the enemy it is to paper, what is? How else do you destroy vellum? Well, the short answer would be that you can’t, not easily, but it can be damaged, sometimes beyond repair, by water. Paper is damaged by water, the average piece of A4 white paper absorbs it and it warps and no amount of ironing will flatten it, hence papers for artists have to be prepared before they are used. Vellum also changes in water, but in a different way.

|

| one of my experiments, immersing vellum in water. I cut this piece from the edge, you can see the corners. Then I left it in water. That’s around a 50% shrinkage. |

The production of vellum is all very natural. It is stretched on a herse and dried under tension and it then stays that way. It is not tanned like leather is, a process that alters the proteins in the skin permanently. Apply water and it will want to go back to how it was. A sheet of vellum immersed in a bucket of water will have reverted to its previous size and shape within fifteen minutes, a dramatic and violent change. However, if the vellum is still in the frame, or stretched tight over something else, and it is then moistened, it will again try to shrink and cockling (lumpiness) will appear where it is trying to shrink, but because it is under tension, it will dry back into its stretched form.

These two startling processes have different uses. The latter is perfect for drums. When consistently hit in the same place, a drum head will stretch and the drum will lose its resonance. To rectify this with a vellum drum head, one merely rubs the whole surface with a wet sponge and leaves it to dry. It will dry and tighten back to how it was when it was new.

The former process has several uses. For instance, furniture. Carlo Bugatti, father of Ettore Bugatti who made cars, used vellum extensively in his designs, decorative and practical. In the construction of furniture vellum is used to secure joints. Wrap the vellum around the joint and wet it. As it is not under tension, it shrinks and it will hold the joint securely.

Another little-known use is for bow strings. A piece of vellum long enough to create a string doesn’t exist, but flat, square sheets weren’t used. Instead, you cut a circle and then you cut around the circumference a millimetre from the edge, working your way inwards in a spiral, and like peeling an apple, you have a long strip. This was then affixed to either end of the bow. This in itself creates a very strong bowstring, but you wet it and it shrinks, giving that much more tension to the bow and a greater range. It dries, it returns to its former size, and you wet it and start again.

|

| Vellum document 1802 |

There are two historical events that I was always curious about and a chat with the general manager, Paul Wright, at William Cowley vellum manufacturer (the only vellum maker in the world that still makes vellum the same way as the Anglo-Saxons) helped to explain them. The first was the dreadful fire that destroyed swathes of the manuscript collection called the Cotton Collection at Ashburnham House, Westminster, London, in 1731. If vellum doesn’t burn, what happened? The vellum itself, the manuscript collection, wasn’t the accelerant that caused the fire to burn. Something else fed the fire - bookcases, carpets, curtains etc. - and the flames were applied to the vellum causing it to degrade. Then there was the water damage from the attempts to extinguish the fire.

|

| Ash Burnham House 1880 |

The other was a new scenario for Paul Wright but he was able to explain how it was possible. In 1347 a letter was smuggled out of Calais which at the time had been besieged by the English for a year. The letter was a plea to the French king to relieve the town, else they’d be forced to surrender to King Edward III of England. When the English attacked the ship carrying the letter in Calais harbour, fearing the letter expressing the dire situation would fall into the hands of the English, it was attached to an axe and thrown into the sea. A English sailor jumped in after it and retrieved it, and it was taken to King Edward.

But how did a letter written on vellum that had been in the sea remain legible? Paul wanted details about how the letter was attached to the axe that I couldn’t supply but it sounded plausible for the letter to have been wrapped around the axe handle and secured with some twine before it was thrown into the water. In which case, Paul explained, as a roll, only two surfaces were exposed to the water (the outer and inner of the roll), and only those would have been subject to water damage, and these surfaces would have covered the rest and protected them, leaving them dry and undamaged. Had the writing only been in the centre of the sheet, it would all have remained perfectly legible. And it would have taken, he estimated, about a quarter of an hour for the exposed surfaces to be damaged, leaving the interior safe for longer than that, giving Edward’s sailor possibly as much as half an hour to fetch up the letter from the floor of the harbour.

Vellum is seen as archaic and irrelevant. Parliament decided in 2017 to stop recording public acts of parliament on vellum. And yet a few years ago the vice-president of Google referred to ‘bit rot’ where files are rendered unreadable through defunct software and called for ‘digital vellum’ to be created to preserve a generation of data from the digital age. Domesday Book is still as legible today was it was when it was written in 1086.

|

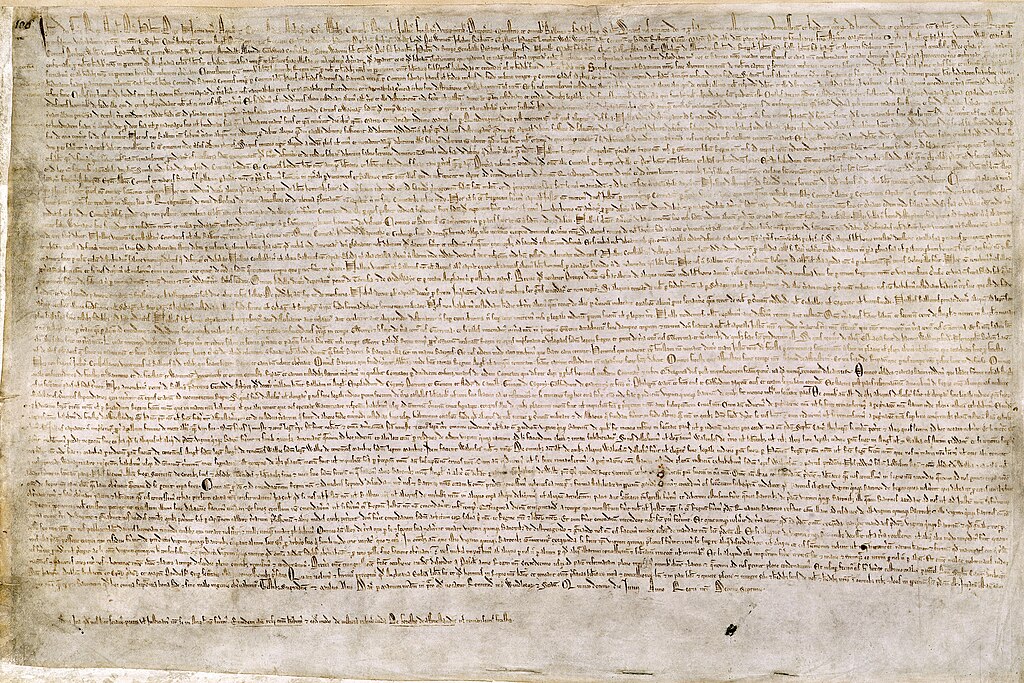

| Magna Carta - again, written on vellum (British Museum) |

In this modern age of digital technology, of cloud storage and digitalisation, data is ephemeral.

Vellum, however, is almost everlasting.

© Nicky Galliers

Fascinating. I checked into vellum for a short story I wrote recently - a bad story. This fills so many gaps in my knowledge. Thank you.

ReplyDeleteGoodness! What a complex thing vellum is. Thank you, Nicky, for a comprehensive post.

ReplyDeleteThis is such an interesting article, Nicky. You know you've now made me desperate to get my hands on a piece of vellum, don't you? I've learned a lot from this.

ReplyDelete