Methods of the Tudor Spies

by Adele Jordan

In a period of 500 years, what might surprise many is that in some ways the world of spying hasn’t changed a lot. If we write of double agents, we conjure memories of the spies in World War Two and the Cold War, who promised allegiance to one side and worked for another. If we talk of spreading disinformation, then the words ‘Fake News’ spring to mind in the current political climate. Speak of ciphers and we think of modern-day encryption software and multiple levels of cyber security, but how did all these things play out in the 16th century, when technology was somewhat different?

When researching ‘The Gentlewoman Spy,’ an espionage adventure about a woman spy working for Francis Walsingham to protect Queen Elizabeth, I had to devote myself to this world of espionage in the Tudor times. It’s a fascinating world of hidden secrets and perpetual lies, used in order to get ahead in the political world.

Francis Walsingham is sometimes referred to today as the ‘father’ of espionage, being Elizabeth I’s spymaster, yet how exactly did his network and other spies operate?

|

| Francis Walsingham |

Ciphers and Codes

The bread and butter of spymasters like Francis Walsingham was ciphers and codes. Messages within their own ranks were exchanged regularly, using coming ciphers, some simple and some incredibly complicated.

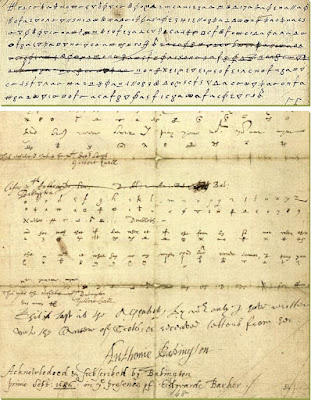

Cipher cards and chart maps could be used as keys, such as the ones that were seized from Mary Queen of Scots and are currently held in the National Archives. Thomas Phelippes was the key codebreaker for Walsingham and was the key mind of decryption during the discovery of the Babington plot, where they caught Mary for her plot against Elizabeth. This incident is one of the best recorded incidents from the 16th century of ciphers at work.

|

| Codes found in Queen Mary's chamber |

After the double agent, Gilbert Gifford, persuaded Mary Queen of Scots to let him handle her communications with an ally of hers, Thomas Babington, Gifford set up a method of communication using a local brewer. When the brewer delivered ale to the castle where Mary was held, Babington’s letters were to be hidden in the cork within the barrel. Gifford then extracted these and gave them to Phelippes to decipher. It was this message that ultimately led to Mary’s downfall, as Phelippes added a message to the bottom of one of Mary’s letters, asking for the names of the six assassins, who were to carry out the plot against Elizabeth, Babington revealed the names. Mary had been caught guilty of treason, writing her own ciphers that had been commandeered by Walsingham’s men.

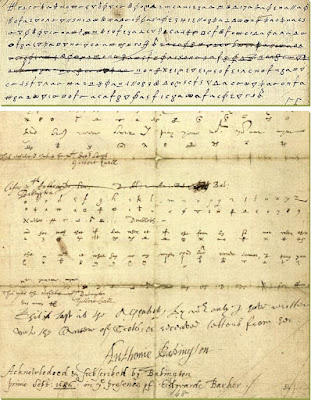

|

| Babington's coded letter |

When Mary’s rooms were searched, papers were found holding the secrets to over 100 different cyphers. One of the most common cyphers used by both Mary and Walsingham’s spies was to shuffle the letters of the alphabet into a different order, so letters stood for alternate letters. If a ‘key’ was provided, with one or two letters known, then the rest could be deciphered. Often, letters would be substituted with numbers instead, and could be deciphered in a similar fashion. It was also known to use codenames within a coded cypher, so Zodiac symbols could be used for names of people. Alternatively, symbols could be used entirely instead of letters, as a nomenclator, using some symbols for letters, and some symbols for very commonly used words and phrases. Anyone who has picked up a puzzle book and given the ‘Codeword’ puzzles a try will see how some of these codes can be broken if you have a ‘key’ or a few letters to begin the transcription.

What makes these ciphers even more ingenious at times was their method of transportation. In Italy the practice of writing messages in lemon juice on papyrus began to spread. When heated over a candle, the message would appear. This soon cropped up in England too, and the same effect could be earned with milk. Evidence remains suggesting that some of Mary Queen of Scots’ most secret communications were written using alum. One of the more peculiar practices mentioned in research is using an ounce of alum and a pint of vinegar mixed together, which when painted on the shell of a hard-boiled egg, will transfer itself onto the white beneath. When the egg is then peeled, the message would reveal itself.

Secret messages were passed throughout the Tudor world, across the continent, between spies and Kings. The interception and protection of these messages was one of the key methods Walsingham and other spymasters of the period used.

Priest Holes

Of course, as fast as the Elizabethan spies were developing methods to find Jesuits priests and Catholic plotters against the Queen, Catholics were developing new ways to hide from them. Here we have one of the most used devices in English literature. Who hasn’t read a murder mystery set in a beautiful English manor, where the discovery of a priest hole suddenly widens the possible suspect list? The real priest holes reveal that where Catholics had to hide was not always glamorous, resulting in cramped and confining conditions for hours an end, but their locations were often ingenious and hard to find.

|

| Oxburgh Hall |

Oxburgh Hall – one of the most famed holes where a priest hole’s entrance is perfectly hidden, disguised by the tiled floor of a garderobe and nestled within a turret. Hiding beneath the very place where residents visited the privy, it might have had its drawbacks, especially due to the smell.

Baddesley Clinton – one of the few holes that’s use is believed to have been documented. Recorded by Father John Gerard, minutes before a mass began in the early hours of one morning in 1590, the house was raided and Catholics were forced to hide in a priest hole underground, flooded with water that reached their ankles. To this day, its entrance can be seen in the kitchen of the house.

|

| Harvington Hall |

Harvington Hall – thought to have more priest holes than any other house in England, boasting seven. Four of these hiding places are set around the grand staircase, and one is set into the staircase itself, only accessible by lifting two of the steps. Another hiding place is in Dr Dodd’s library, opened by turning what appears to be a solid timber beam set in the wall. When the beam is lifted, a very narrow gap presents itself, possible for a thin man to hide inside. Thought to be one of the earliest holes in the Hall, above the bread oven in the kitchen there is a small gap stretching just over 5ft by 3ft, accessible through a trap door in the South Room. I imagine the priests were not lining up to hide in this particularly toasty hiding spot.

Torture

It’s an uncomfortable fact that torture was an integral part of spying. Both in Britain and in the continent, records survive showing some brutal use of instruments that today make us shudder. Here are some of the instruments that we know were in use. Fair warning, if you do not like reading of these instruments, best skip over the bullet points below.

• The Rack – one of the most recognisable torture instruments from the era and known to be used by the Spanish Inquisition. The prisoner was tied to a wooden structure, resembling a sort of ladder, and was then stretched using cranks and cogs.

• The Boot or the Scarpines – the prisoner’s feet and lower legs were placed into iron boots where wooden wedges were driven between the boots and the prisoner’s limbs.

• The Breaking Wheel – the prisoner was tied to the wheel and their torturer would take a hammer to their limbs. Other ways of using the wheel included tying the feet and hands to struts beyond the wheel, then turning the wheel to stretch the body.

• The Sacvenger’s daughter – a particularly brutal one that is known to have been used during Henry VIII’s and Elizabeth I’s reigns. Using a hoop of iron attached to long metal rods, the device was designed to force the prisoner into a crouched position, and then just continue to bend them in half.

There are many more torture devices used throughout history, but these are some of the ones we know were used in the Tudor period. As we now know, it may not have always made someone speak the truth but could have forced a lie in the hope it would end the pain.

Double Agents and People

It’s indisputable that one of the most effective methods of the espionage world was to turn a spy’s loyalty, and there are multiple examples of this being achieved in Britain alone.

• Walsingham persuaded Gilbert Gifford, a man previously loyal to the Catholic cause, to work against Mary Queen of Scots, ultimately leading to her downfall in 1586. His loyalty by the end of his life is still unclear, as he acted for both Protestants and Catholics throughout his life.

• Isabella Hoppringle, the prioress of a convent on the English and Scottish border in the first half of the 16th century may have spied for both the English and the Scottish, acting loyal to both sides in order to protect her convent and the women who lived there. She managed to keep the convent safe and untouched, even when the English and Scottish fought a few miles from the convent front door in the Battle of Flodden.

• William Parry was originally a loyal spy to Walsingham and Elizabeth, sent to the continent in the latter half of the 16th century to spy on Catholics who had fled from Britain. Yet by 1583, it was clear he had been acting for both sides, and a letter was discovered showing he had written to a Roman cardinal, pledging his loyalty to the Catholic church. His double life was not as successful as Hoppringle’s, and in 1585, he was hanged, drawn and quartered for his betrayal.

|

| Catherine de Medici |

If we turn attention aware from Britain to France, we see that the French court was held under the power of one woman in particular, Catherine de Medici, the mother of the King of France. By recruiting women to be part of her ‘flying squadron’, or ‘escadron volant’ in French, she encouraged these women to act as her eyes and ears around the court, feeding information back to her. What was more, she persuaded some of her squadron to be seductresses, in order to hold power over the men in the court. Madame de Sauve, one of her recruits, was persuaded to seduce Henry of Navarre and the Duke of Alençon, the latter not only being Medici’s own son, but both being of considerable influence at court, who distracted themselves from political matters by arguing over Madame de Sauve.

When looking at the research of this era, what becomes plain is the ingenuity of the spymaster that led to the different methods of their intelligencers. Walsingham was a man of political manipulation, and was ruthless, known to enact torture, but he was also zealous in his protestant beliefs, and there is no evidence to suggest he ever encouraged the use of seduction such as Medici did. Perhaps his religious beliefs held him back, or maybe he did not see the use as Medici did. By using people rather than technology, Medici earned ears all over the French court, and with it, came her power.

Ciphers, invisible ink, priest holes and double agents, all were manipulated under the aim of protection. Medici claimed to be protecting her son on the throne, and Walsingham’s aim was to protect his Queen, a monarch he believed in. Yet it cannot be denied that through their methods, they gained power for themselves as well as their causes. Walsingham raised himself to sit on the privy council under Elizabeth’s reign, and with his death, those left behind struggled to make the spy network what it once was. With the death of Medici too, her ‘flying squadron’ dissipated, and the squadron’s influence faded.

What is clear is that wherever there was a want of power, guile was not far behind. Using spies, double agents, misinformation and ciphers, that power could be obtained.

© AdeleJordan

Sources

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you for leaving a comment - it should appear soon. If you are having problems, contact me on author AT helenhollick DOT net and I will post your comment for you. That said ...SPAMMERS or rudeness will be composted or turned into toads.

Helen